Last Updated on August 31, 2023 by David

Why rethinking productivity will help you win the market.

Productivity is dead. More accurately put, the definition of productivity is dead. Set aside the differences in how people from around the globe measure and value productivity, the notion of “overworking” or “work-life-balance” is outdated because we’ve been conditioned to be overly reactive to the implications of diminishing returns on productivity.

Traditional productivity pundits say that for every extra hour we work, we get diminishing returns. Working 9, 10, or 11 hours is less effective per hour than working 3, 4, or 5 hours, but we need to be realistic about the implications of incremental differences in overall output. What traditional productivity rules don’t mention is the factor of relative success, or how successful people are in their respective circumstances after productivity is taken out of the equation.

In a free market, every incremental advantage can tip a given competitor to win a majority of the market. So when your competitor is working 41 hours instead of your 40 hours, he or she might win 90% of the share of market. American football is a good example of this. Statistically speaking, the team that gets on average 3 yards per rush is going to lose to the team that gets on average 3.1 yards per rush. Every incremental competitive advantage can mean taking the lion’s share of the market (or job promotion, or academic funding, or major lead, etc). Here at Reamaze, a SaaS company, we know this all too well.

If we apply this concept to an industry like eCommerce, the store that does just a little bit better than the next store, whether it’s pricing or return policy or customer service, is going to get the incremental sales. Iterated over millions of encounters, this adds up to a huge differentiator. These problems are very real in eCommerce where if you’re not putting your best foot forward on every little detail, you might miss out on the entire market. If your store is only 90% as good as someone else’s store, you don’t get 90% of their sales volume. You’re lucky to get just 1%. In a competitive field, incremental output can mean success vs. failure, which is a binary output.

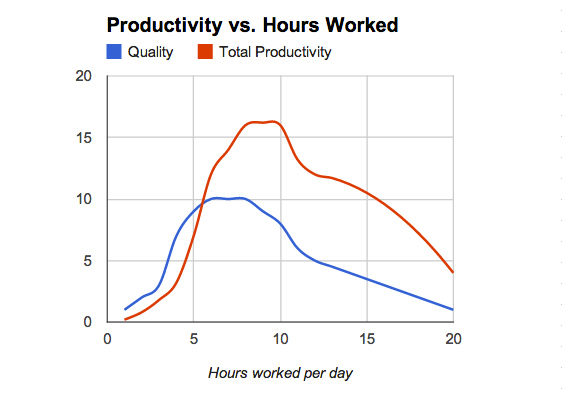

Here’s a quick look at a typical productivity graph:

In a vacuum, it would seem that productivity has taken a turn for the worse at roughly the 8-hour mark, corroding slowly overtime. However, as an entrepreneur, are the results between hour 9 and 15, any less real? Are the benefits reaped from working at a marginally decreased quality not impactful to your business or putting you ahead of your competitors? The issue with graphs like the one above is one of realistic productivity.

“Real” productivity is inherently difficult to measure because:

People lie about how much they work. They lie to conform to expectations and lies go in multiple directions… Cross-country studies will also often impute the legal work hours to workers in different countries even though these may not correspond to hours worked… Even well-meaning self-reports are terribly inaccurate. People count time spent at work even though they spent a lot of it on non-productive activities. It can even be hard to define the boundary between work and non-work… — Luis Coelho, Computational Biologist at EMBL

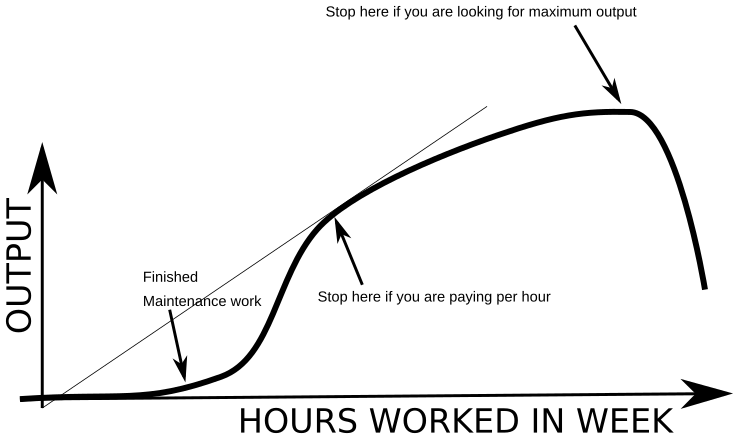

This graph below represents productivity when looked at from a different perspective.

Image from Luis Coelho

Luis makes a good argument for working more than what is culturally defined as “the right number of hours to work”: maximum output. If you hire employees based on an hourly wage (like Amazon’s many departments) it makes perfect sense for employees to take off as the average maximum output is reached and quality starts corroding away. Working beyond that and you (as the employer) will start to see a negative tradeoff between wages paid and benefits reaped. As entrepreneurs, where the benefits of an extra hour’s worth hustle can only be achieved at “maximum output” rather than “average maximum output”, we owe it to ourselves to make that commitment.

If you are hiring people by the hour, you want them to work to the point where output/hour is optimized, which is the traditional justification for why companies should have shorter work weeks. However, this can be well below the point at which output is maximal.

Another thing to consider is whether people who adopt a “working more is bad for you” mentality are employees or entrepreneurs. Because as any budding entrepreneur understands, there’s no such thing as work-life balance. When Amazon announced its 30-hour work week plan for its employees, the main arguments for shortened hours focused around terms such as “burnout”, “flexibility”, “arbitrary”, “human limits”, and of course “productivity”.

Beyond five to six hours of focused concentration, productivity either plateaus or declines. What this seems to indicate is that the extra two to three hours in the standard, full-time workday (or more, for the multitudes of employees who are banking tons of overtime weekly) are not very productive. The result is a waste of the employee’s time and the employer’s money. — Forbes.com

The keyword in the excerpt above is employer. Employers should focus their attention on building ideology, rapport, philosophy, and culture and less attention on exacting hours worked. Because in an ideal world, both employees and employers would work exactly the amount they need to work to deliver on specific goals.

And yes, working more means your productivity tapers off and eventually drops but there might be ways to compensate for simply “working more”. Rather than squeezing every drop left from the productivity bucket, there are other things a store owner can do to “hustle”. Perhaps spend just a little extra than competitors to get higher search rankings (e.g. rank 1 might only be $0.50 higher than rank 2). Perhaps it’s spending money on staffing, etc.

Running an eCommerce business, or any business for that matter, is a fierce competition in the purest form. Just like in sports, academia, or culinary arts, hustlers willing to go the extra mile or quarter mile will likely win the game because “in a competition, payoffs can be heavily non-linear”. Every incremental hour worked may not have the maximum of returns but every incremental hour worked can yield significant cumulative long term effects. An extra 15-minutes of studying here, an extra 15-minutes of optimizing your ads there, an extra 15-minutes of upping the fidelity of your graphics somewhere else, or an extra 15-minutes of modifying your site’s customer service experience adds up to an hour of someone else not doing what you’re doing. Hustling with just a 1% advantage can win you an entire market if you’re willing to put in the work. And your competitors? Well, they can fight for the scraps.

Interested in what else we have to say? Make sure to recommend this article by clicking the heart and follow us for more stories about startup life, customer service, and tips on treating customers right.

You can also find our multi-brand, multi-channel customer service platform at https://www.reamaze.com. Follow @reamaze.